Dispersed Organic Matter

(DOM)

Dispersed Organic Matter — History in Microscopic Pieces

Dispersed Organic Matter (DOM) is not simply “organic debris in sediments.”

It is the smallest record of biological input, preservation conditions, and burial evolution.

Its composition, morphology, and transformation pathway make DOM one of the most powerful tools for interpreting basins, reservoirs, and environmental archives.

DOM is where the story begins — and sometimes where it ends.

Where DOM comes from

DOM may originate from:

terrestrial vegetation,

lacustrine biomass,

marine planktonic communities,

or mixed systems.

The pathways by which this material is introduced—water column productivity, transport, oxidation, biodegradation, sedimentation—determine its initial quality.

But deposition is only the opening chapter.

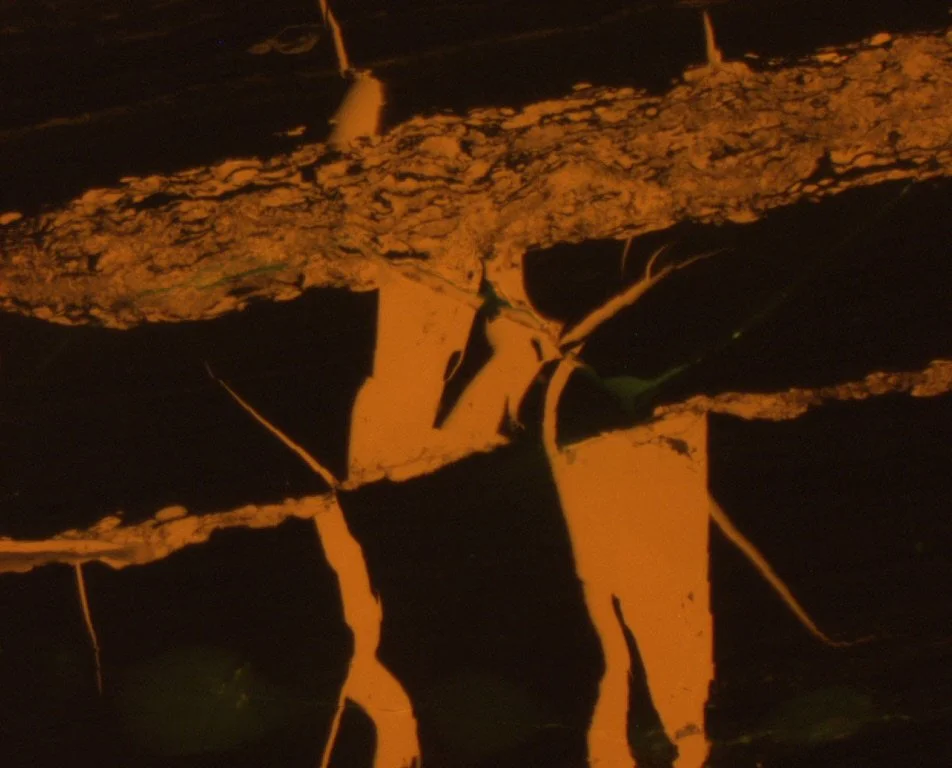

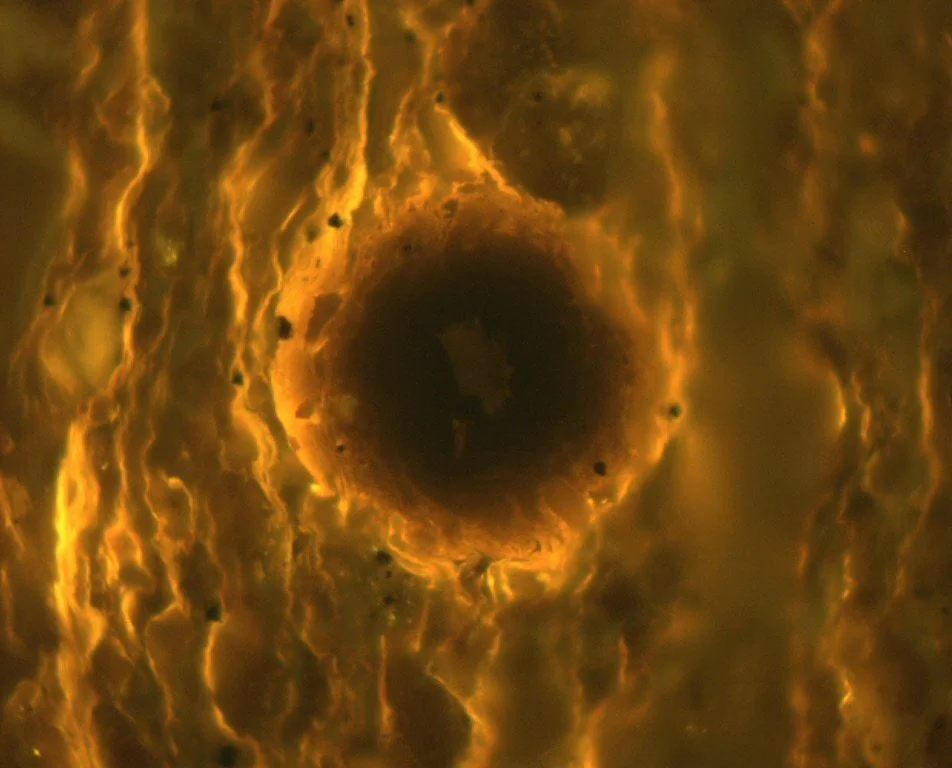

Bituminite dispersed in the matrix and solid bitumen infilling foraminifera tests. Toolebuc Formation, Eromanga Basin, Australia. Photomicrograph taken in reflected white light.

Preservation is selective

Organic material survives only under favourable conditions:

limited oxygen exposure,

adequate sedimentation rate,

minimal microbial attack,

restricted physical reworking.

These filters determine what survives and what is lost, leaving behind patterns in reflectance, fluorescence, and morphology that carry direct paleoenvironmental meaning.

DOM does not simply exist; it is what was able to persist.

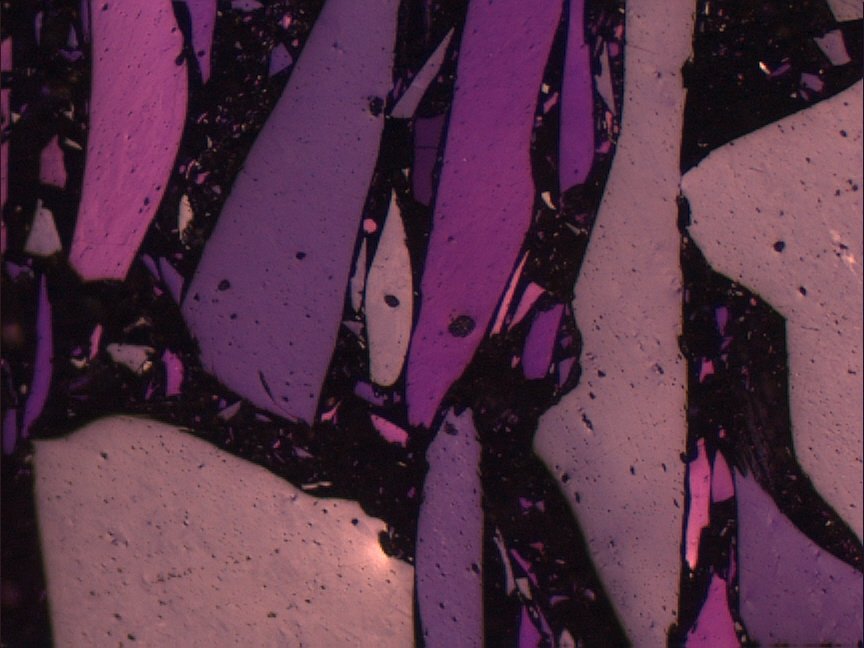

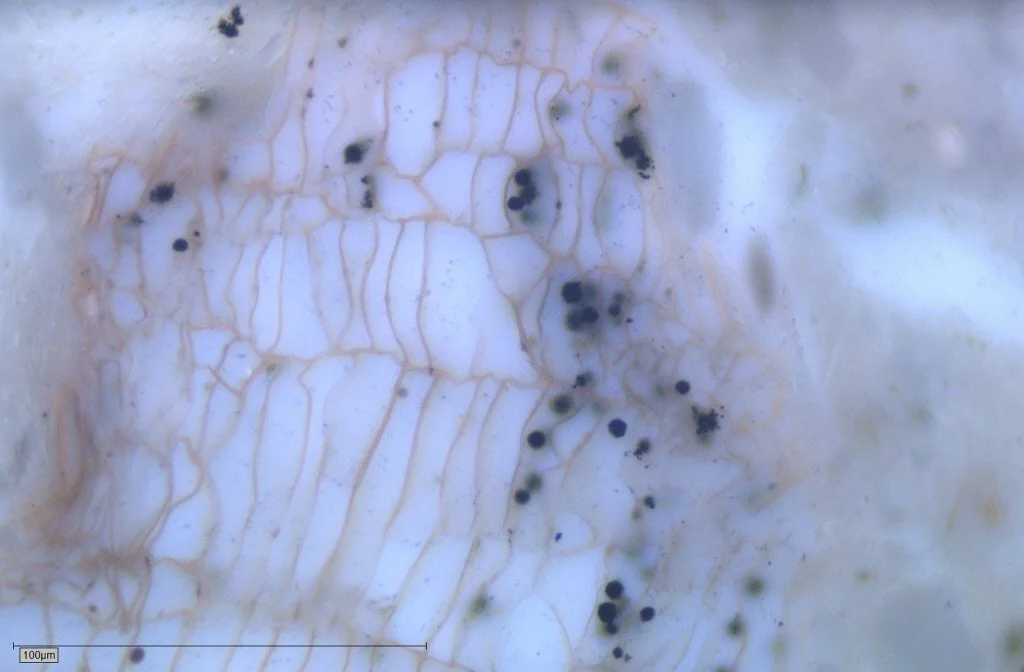

Lamalginite and thucholite. Barney Creek Formation, McArthur Basin, Australia. Photomicrograph taken in fluorescent mode.

From precursor to hydrocarbons

With burial, DOM undergoes diagenesis and maturation.

Thermal evolution reorganizes organic structures, expels volatiles, and progressively converts precursors into solid bitumen and liquid/gaseous hydrocarbons.

Source rocks are not “containers.”

They are reactors—their DOM composition governs:

onset of hydrocarbon generation,

richness and type of products,

migration pathways,

efficiency of charge.

This transformation also leaves behind solid bitumen, a durable signature of generation events even after fluids have moved on.

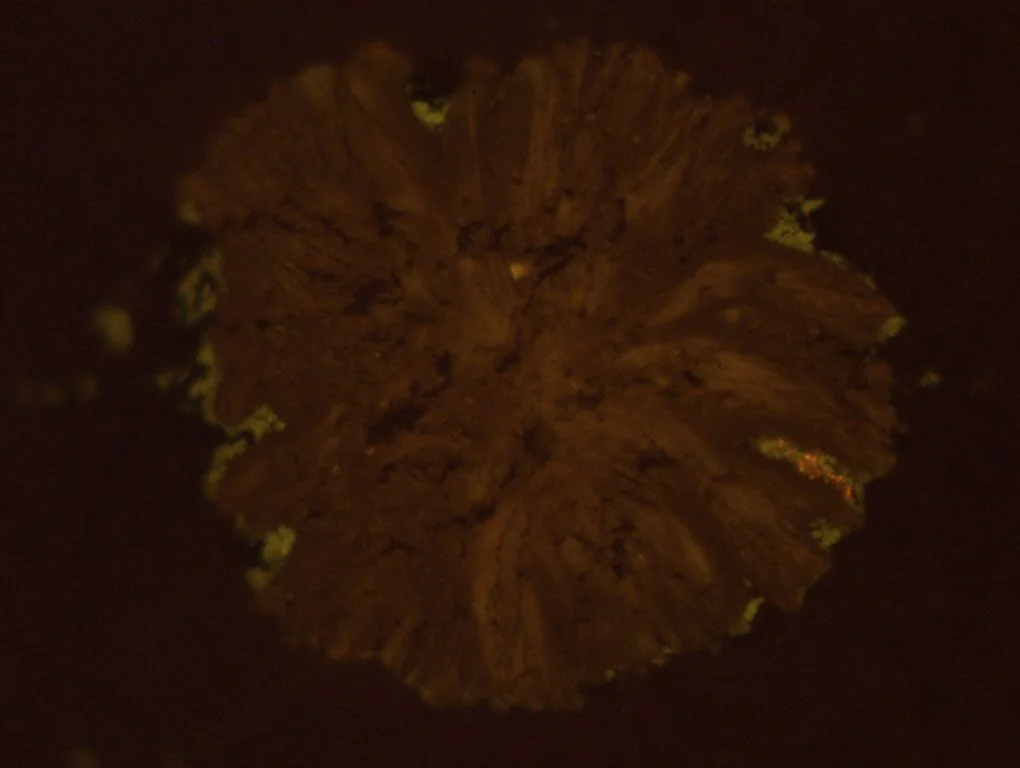

Pre-textinite in recent river stream sediments. New Zealand. Photomicrograph taken in flourescent mode.

DOM as evidence

DOM is valuable because it captures processes larger than itself:

Paleoredox and depositional environment

Oxidized inertinites, algal material, bacterial residues, cuticles, resinites.Maturation levels

Optical changes, fluorescence suppression, reflectance evolution.Fluid circulation and thermal anomalies

Localized alteration, hydrothermal episodes, injection-related modification.Sediment accumulation rates

Preservation vs destruction balance.Hydrocarbon history

Migration pathways, secondary cracking, bitumen residues.

DOM is the closest thing geology has to a forensic archive.

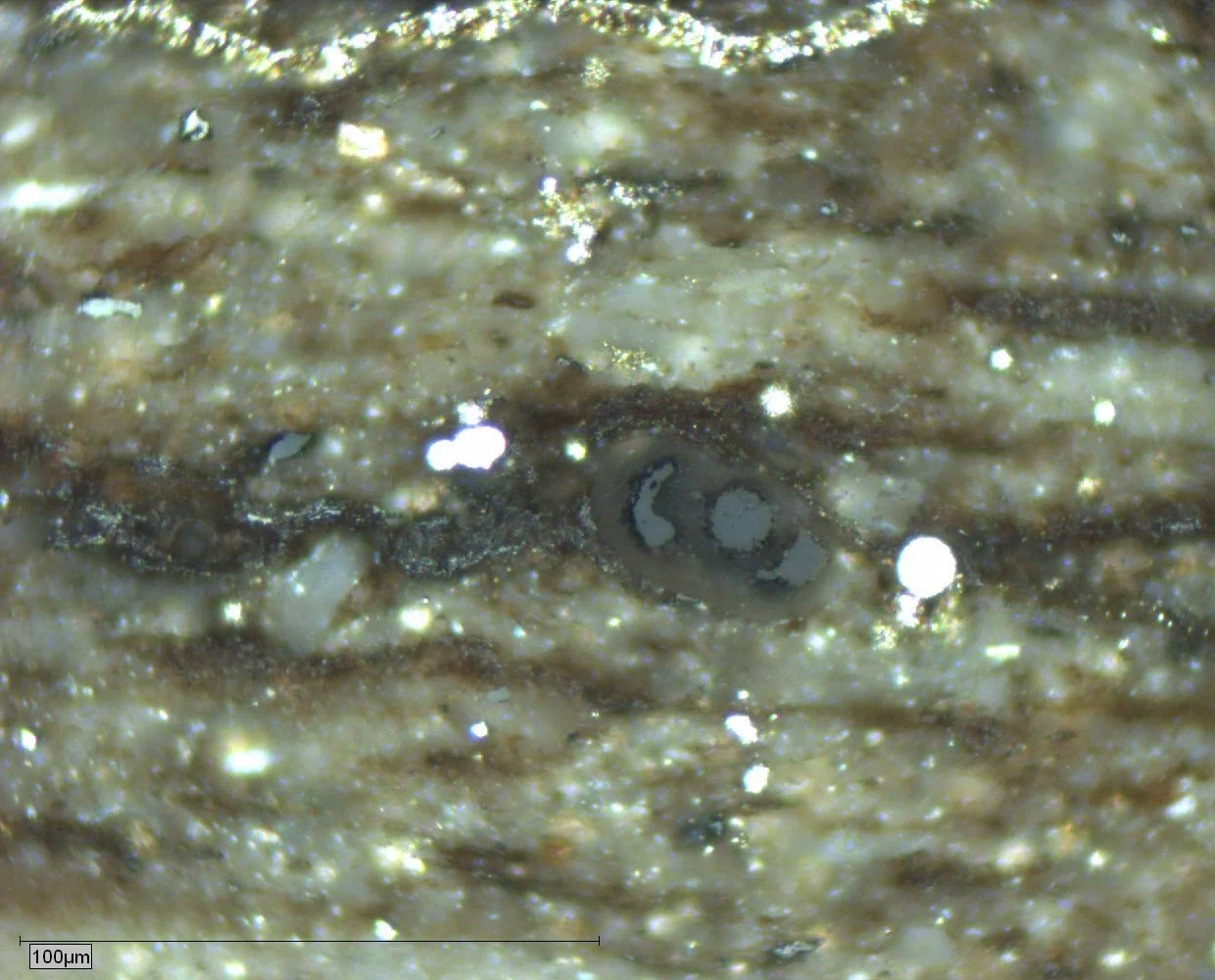

Charcoal derived from florest fire found in recent river stream sediments. New Zealand. Photomicrograph taken in reflected white light.

What CarbonMat examines

We do more than catalogue particles.

Classification of DOM populations (terrestrial vs marine vs mixed)

Optical evaluation of maturity trends

Identification of oxidation, biodegradation, and wildfire signatures

Solid bitumen mapping and characterization

Integration with geochemistry, Raman, FTIR, and mineral data when relevant

We interpret what the DOM is telling you about the rock and its past, not merely what species it resembles.

Where this matters

Source rock evaluation

Reservoir characterization

Unconventional resources

Basin modelling

Paleoenvironmental reconstruction

Contamination and environmental studies

Academic research spanning organics and minerals

DOM is a small component with disproportionate explanatory power.

If you need clarity on what your DOM is saying

Tell CarbonMat the context of your samples and your objectives.

We will determine the analytical route that yields the most insight.