Coal

Coal — A material of structure, history, and behaviour

Coal is not just “plant matter that turned into fuel.”

It is an archive of biological input, diagenesis, and geologic forcing.

At the microscopic scale, this archive is expressed as maceral assemblages whose composition governs performance, reactivity, and thermal behaviour.

Understanding coal begins with structure.

What petrography reveals

Coal petrography examines the microscopic constituents of coal: vitrinite, inertinite, and liptinite, along with mineral components.

These components are not merely descriptive. They are diagnostic of:

rank evolution and thermal maturity

depositional environment

oxidation, wildfire, or hydrothermal alteration

coking behaviour and coke failure

variability in ash yield and degradation

influence of minerals on processing outcomes

Petrography answers why a coal behaves the way it does — not simply what it contains.

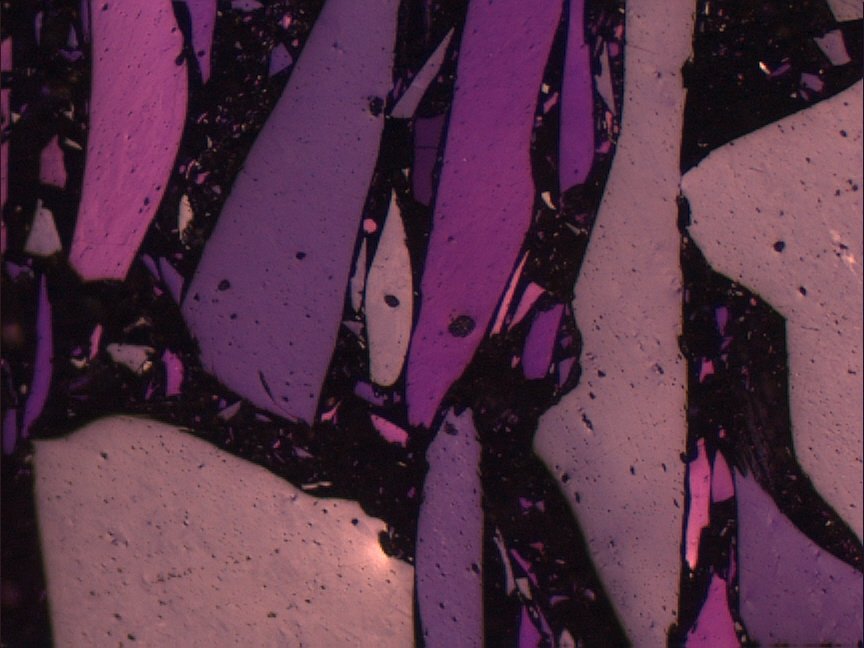

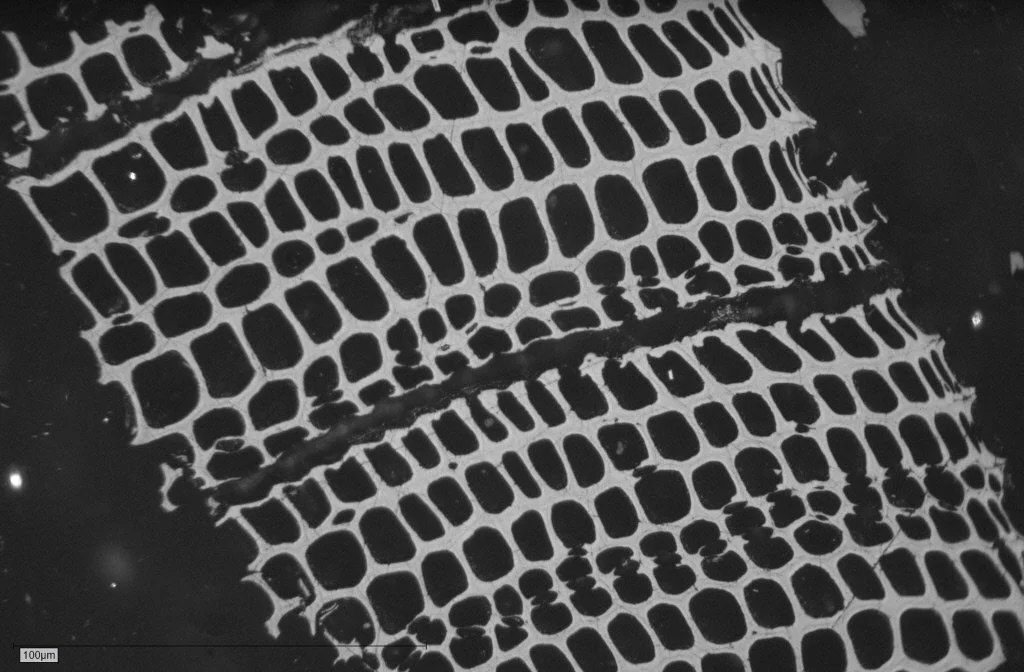

Coal macerals: inertinite (white), vitrinite (grey), liptinite (dark grey/brown). German Creek Coal Measures, Bowen Basin, Australia. Photomicrograph taken in reflected white light.

Rank is not a number — it is a trajectory

Reflectance is widely used to estimate rank, but it is not a static property.

It captures transformations driven by:

temperature

pressure

time

fluid interaction

strain and deformation

A histogram of vitrinite reflectance incorporates heterogeneity and records what the rock has endured, not just its current state.

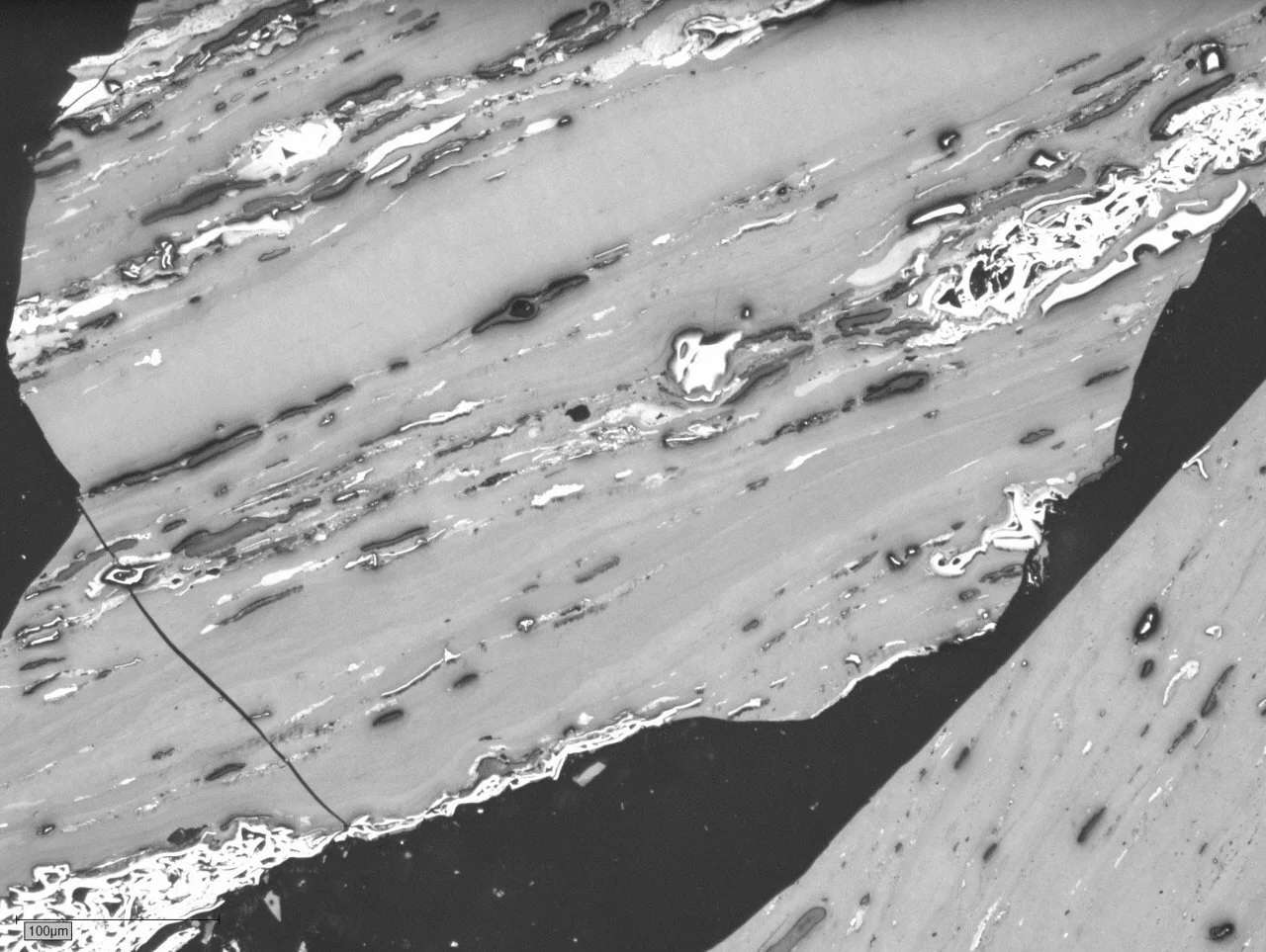

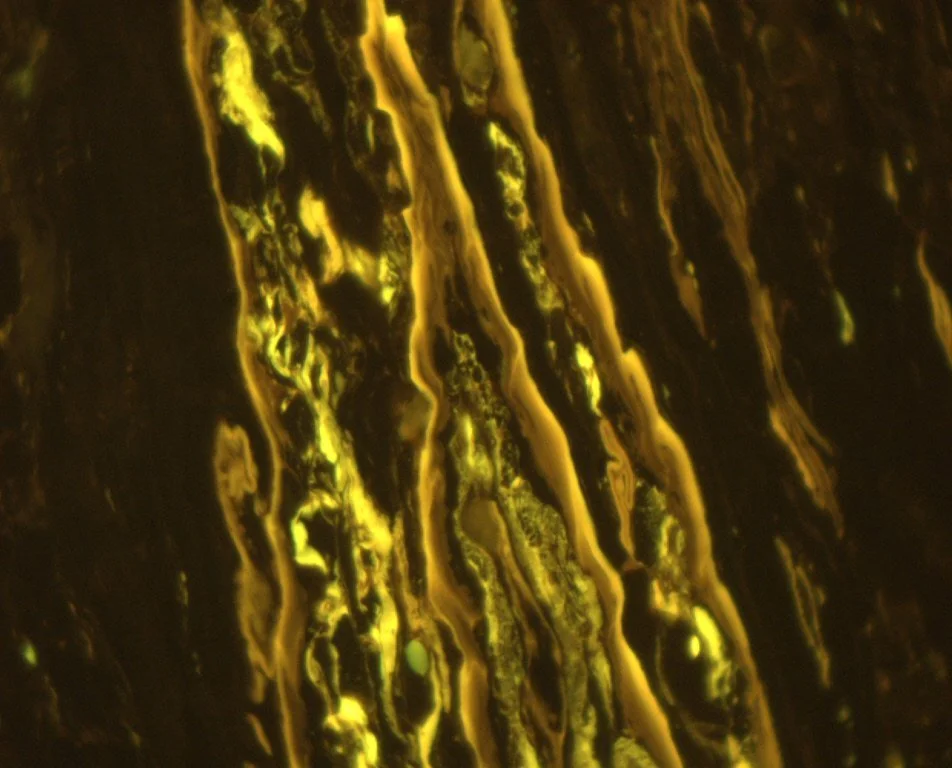

Cutinite (from the liptinite group) representing preserved leaves. Walloon Coal Measures, Surat Basin, Australia. Photomicrograph taken in fluorescent mode.

Composition controls application

Different maceral groups push coal toward different uses:

Vitrinite-rich coals: reactive; used in metallurgical and thermal pathways

Inertinite-dominant coals: resistant; linked to paleofire, oxidation, coke anisotropy, and char behaviour

Liptinites: hydrogen-rich precursors influencing liquefaction, devolatilization, and unconventional carbon products

The maceral balance informs design decisions, not theoretical classifications.

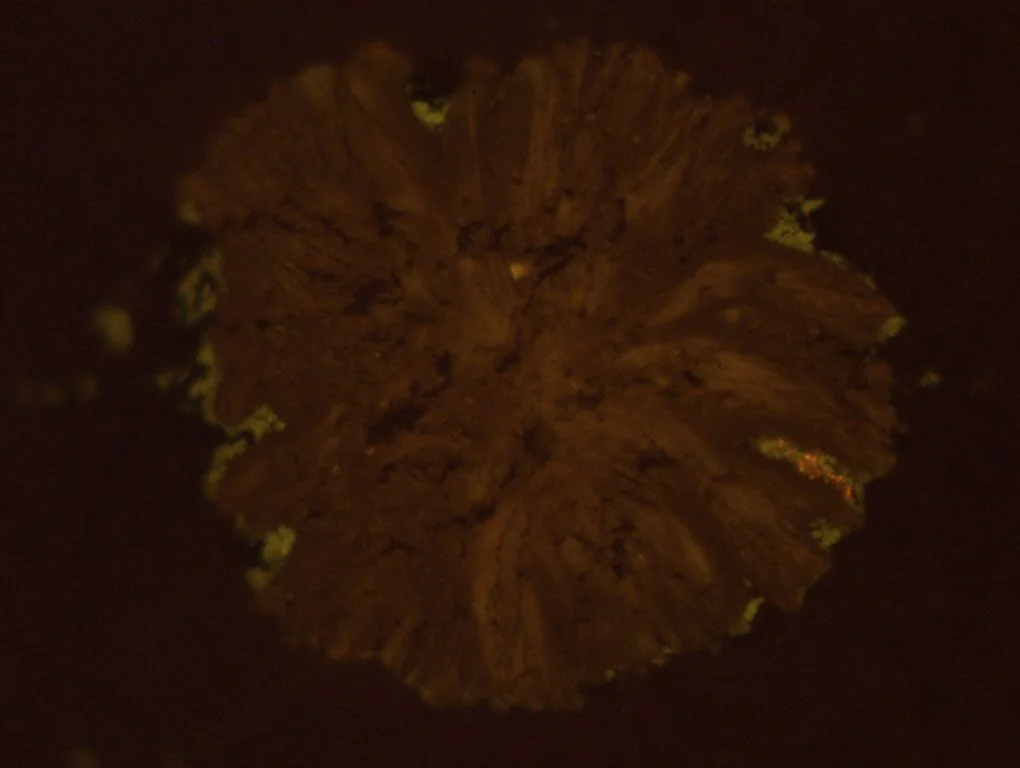

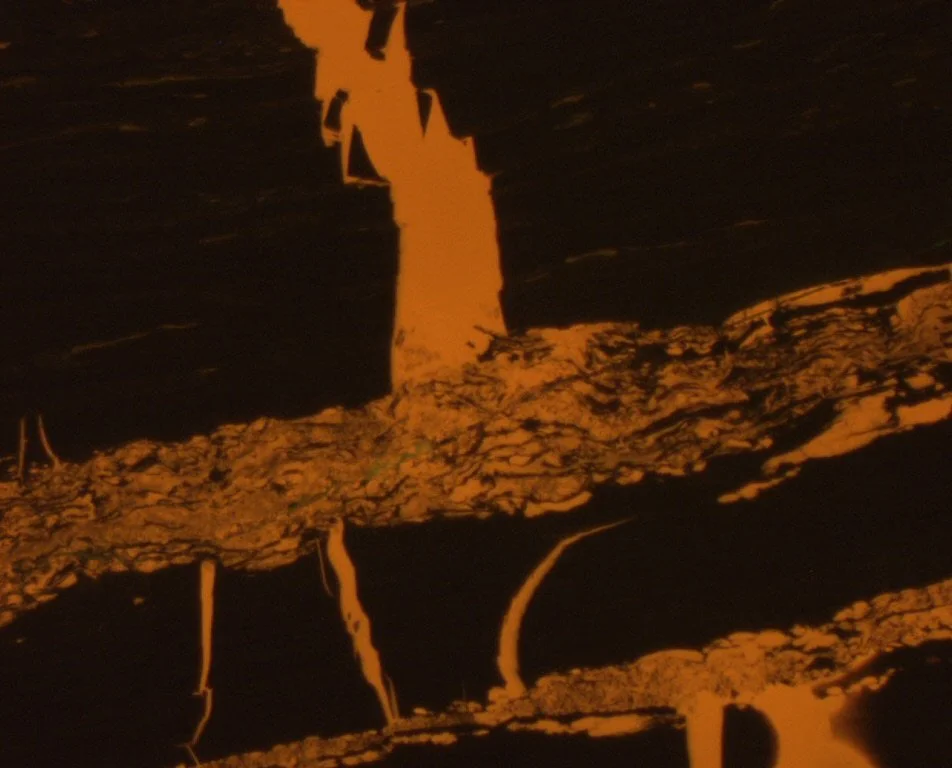

Exsudatinite filling fractures. It is a indicator of oil generation in coal. In this case, exsudatinite is being generated from resinites. Laura Basin, Australia. Photomicrograph taken in fluorescent mode.

Why this matters

Coal analysis is routinely reduced to proximate/ultimate values or bulk geochemistry.

These alone cannot explain:

unanticipated ash

variable coking behaviour

blend instability

anomalous devolatilization

failure during combustion or gasification

Microscopy reveals the causes, not just the symptoms.

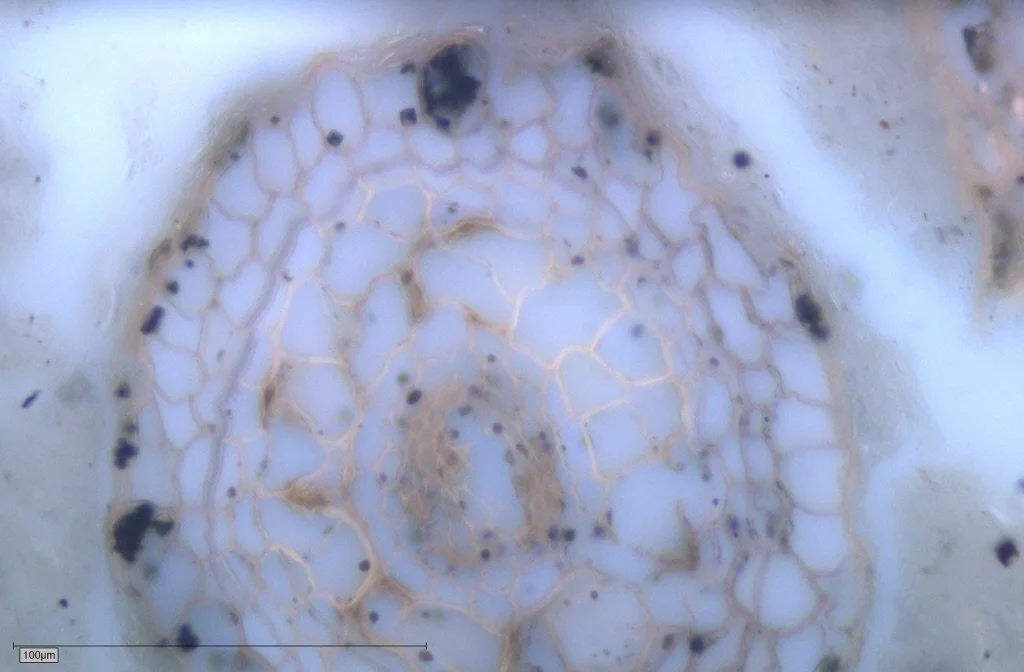

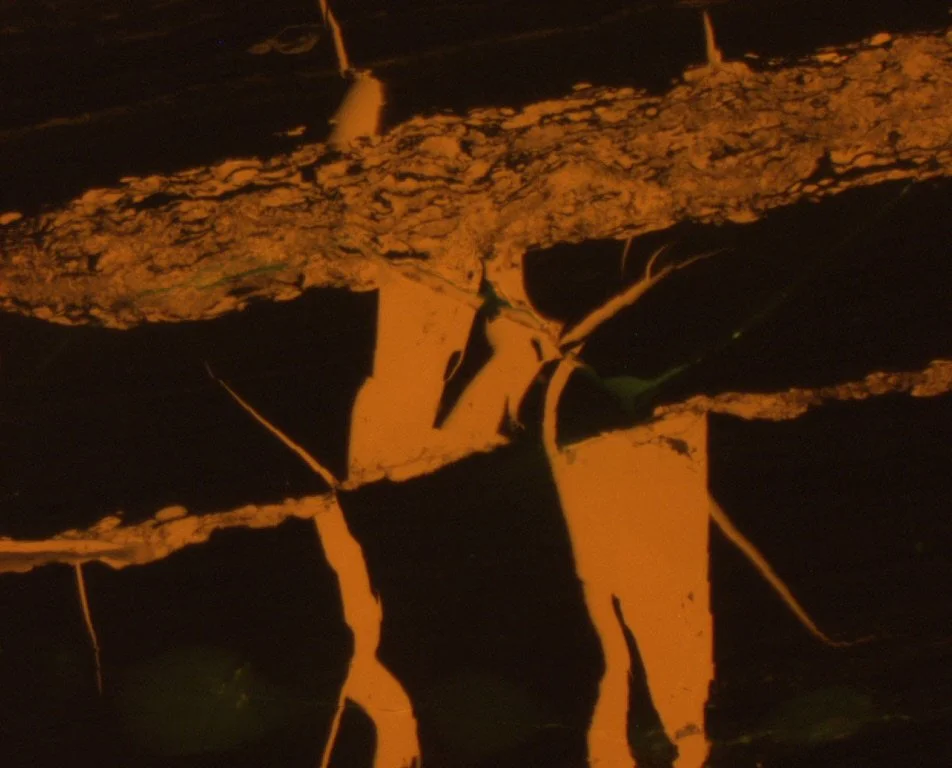

Fusinite maceral showing tissue preservation. Possible origin from paleofires. Location unknown. Photomicrograph taken in reflected white light.

What CarbonMat does with coal

Vitrinite reflectance measurements (ISO/AS compliant)

Maceral group and subtype identification

Mineral matter mapping and interpretation

Alteration diagnostics (oxidation, thermal events, wildfire signatures)

Integrated analysis with FTIR/Raman/SEM-EDS when required

You receive:

quantitative data

interpretive insights

implications for your operation or research

Not descriptions — meaning.

Typical applications

Rank validation for resource reporting

Coal quality variability within a seam or mine block

Coke performance issues and degradation

Optimization of blending strategies

Basinal studies: thermal history, fluid circulation, burial models

Academic research requiring interpretation, not just data

Want to understand what your coal is really telling you?

Share your context and objectives.

CarbonMat will assess feasibility and provide a pathway to insight.