Good to Know Series - 10 - Working with Deep Time — Organic Matter in the Barney Creek Formation

One of the defining aspects of geology is its engagement with deep time. Ancient rocks preserve records of tectonic cycles, ocean chemistry, atmospheric evolution, and early life, allowing us to reconstruct Earth systems far removed from present-day conditions. Among these archives, Proterozoic sedimentary successions provide particularly valuable insights into the early evolution of organic matter and petroleum systems.

The Barney Creek Formation, part of the McArthur Group in the McArthur Basin (Northern Territory, Australia), was deposited at approximately 1.64 Ga. It belongs to a broad interval commonly referred to as the “Boring Billion” (ca. 1.8–0.8 Ga), a term used to describe a period of relatively subdued biological and geochemical change compared to the dramatic transitions before and after. Despite the name, this interval captures critical processes that shaped later Earth history.

During deposition of the Barney Creek Formation, atmospheric oxygen levels were significantly lower than today, while CO₂ levels were higher. Marine environments were commonly characterized by anoxic to euxinic conditions, particularly in restricted basins. At the same time, tectonic reconstructions suggest that the Columbia (Nuna) supercontinent was progressively fragmenting, with Rodinia beginning to assemble, although the timing and mechanisms remain debated.

Importantly, not all basins behaved the same way. While many shallow marine settings experienced sulfidic, nutrient-poor conditions, some intracontinental basins may have remained sulphur-limited. Variations in redox conditions and nutrient availability likely exerted strong controls on microbial ecosystems. These spatially heterogeneous environments may have played a role in fostering early biological diversification and set the groundwork for later evolutionary expansions.

Organic matter preserved in the Barney Creek sediments represents some of Earth’s earliest biosignatures. This organic matter is also responsible for one of the oldest known petroleum systems, with hydrocarbons generated during burial and potentially retained for more than 1.5 billion years. Although long-term trapping is plausible, secondary migration and remobilization cannot be excluded and are supported by petrographic observations in some intervals.

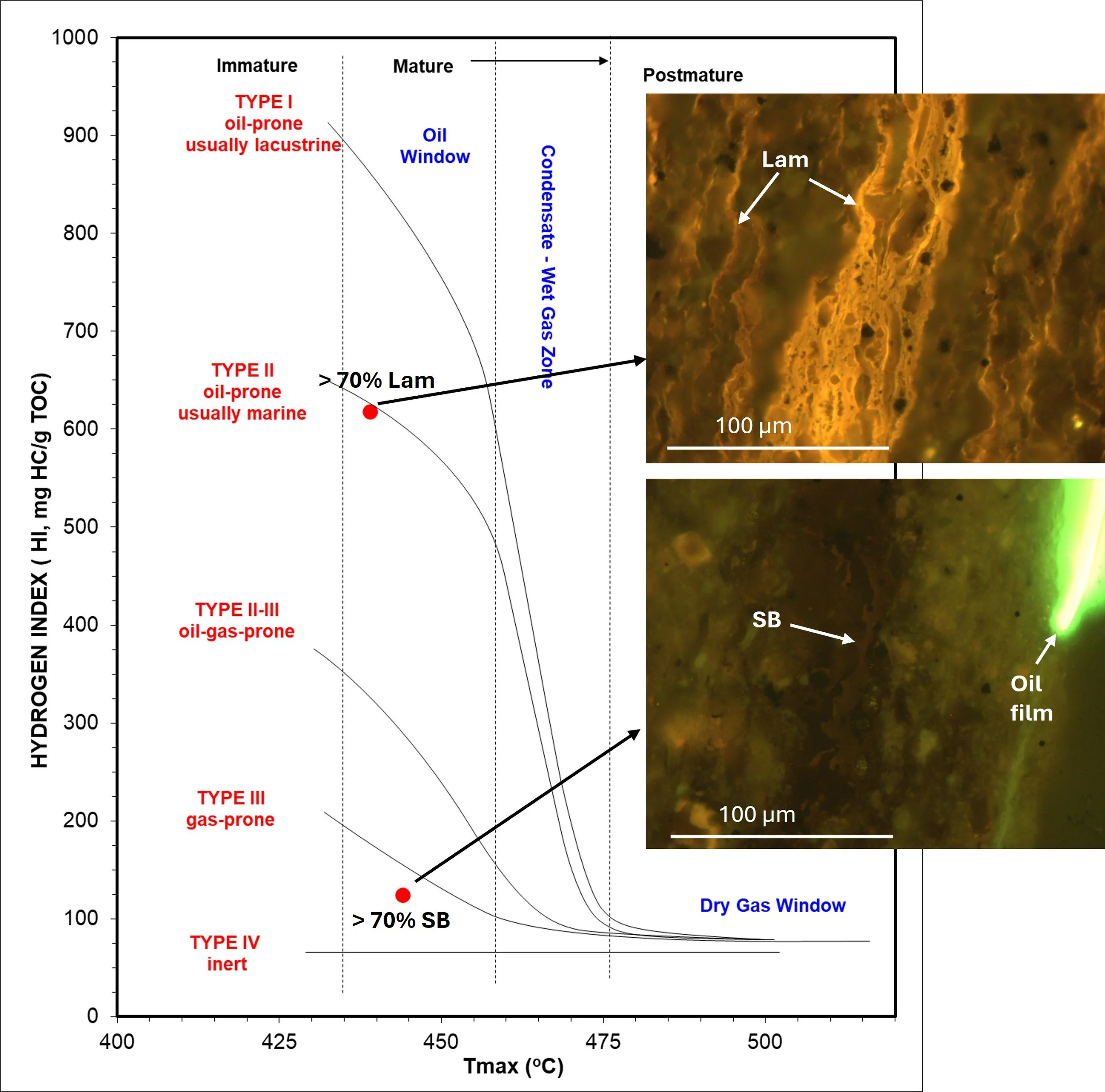

Pseudo-van Krevelen diagram of two samples from the Barney Creek Formation, McArthur Basin, Australia.

Thermal maturity data indicate significant variability across the formation. In certain locations, pyrolysis Tmax values suggest immature conditions or the onset of the oil window, whereas in others the organic matter is overmature and gas-prone. These differences are likely driven by geological factors such as variable burial depth, structural history, and fluid circulation rather than a single basin-wide thermal event.

From a petrographic perspective, the organic matter assemblage is relatively simple. The dominant component is lamalginite, consisting of laminated or filamentous organic matter derived from microorganisms, with little preserved morphology. This material corresponds to Type I–II kerogen. Where hydrocarbon generation has occurred, solid bitumen is also present, either as an in-situ transformation product of lamalginite or as migrated material occupying pores, fractures, and voids.

Geochemical data are consistent with these observations. On pseudo–van Krevelen diagrams, samples with abundant, highly fluorescent lamalginite plot at higher Hydrogen Index (HI), while samples dominated by low-fluorescence solid bitumen show lower HI values. Interestingly, samples from the same drill core, separated by hundreds of metres, can exhibit markedly different kerogen characteristics while maintaining similar Tmax values.

This raises an important interpretive challenge. The Barney Creek Formation predates the evolution of higher plants and therefore lacks true vitrinite (Type III kerogen). Any apparent Type III–like signature must result from the thermal alteration of algal organic matter and hydrocarbon cracking. Conventional maturity models, largely calibrated on Phanerozoic, plant-derived kerogens, may not fully capture the kinetic behaviour of pre-plant organic matter. Differences in biochemical precursors and degradation pathways may partly explain why Tmax does not always track HI as expected in these ancient systems. This remains an active area of research.

Studying formations like Barney Creek provides a long-view perspective on how organic matter is deposited, transformed, and preserved under conditions very different from those of younger sedimentary basins. Extensive work by the Northern Territory Geological Survey has advanced understanding of the Barney Creek Formation, particularly its links between organic-rich sediments, hydrocarbon generation, and mineral systems such as those associated with the McArthur River Mine.

Some reading suggestions:

Brasier, M.D., Lindsay, J.F., 1998. A billion years of environmental stability and the emergence of eukaryotes: New data from northern Australia. Geology 26, 555-558.

Crick, I.H., 1992. Petrological and maturation characteristics of organic matter from the Middle Proterozoic McArthur Basin. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 39, 501-519.

Greenwood, P.F., Brocks, J.J., Grice, K., Schwark, L., Jaraula, C.M.B., Dick, J.M., Evans, K.A., 2013. Organic geochemistry and mineralogy. I. Characterisation of organic matter associated with metal deposits. Ore Geology Reviews 50, 1-27.

Javaux, E.J., Lepot, K., 2018. The Paleoproterozoic fossil record: Implications for the evolution of the biosphere during Earth’s middle age. Earth-Science Reviews 176, 68-86.

Lyons, T.W., Reinhard, C.T., Planavsky, N.J., 2014. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315.

Summons, R.E., Powell, T.G., Boreham, C.J., 1988. Petroleum geology and geochemistry of the Middle Proterozoic McArthur Basin, Northen Australia: III. Composition of extractable hydrocarbons. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 52, 1747-1763.

Northern Territory Geological Survey Publications: https://geoscience.nt.gov.au/gemis/ntgsjspui/handle/1/81425