Things About Me Series – 03 – I look under the microscope, and I know things.

I love microscopy. I love sitting at the microscope and studying samples. It is my quiet place. People I work with often say that I have a sharp eye—that I see things no one else notices. Most of the time, this is actually true. For me, petrography is like assembling a puzzle or solving a detective case. Each sample is unique. You have to pay attention to what the sample is telling you. Because every sample has a story—you just have to listen.

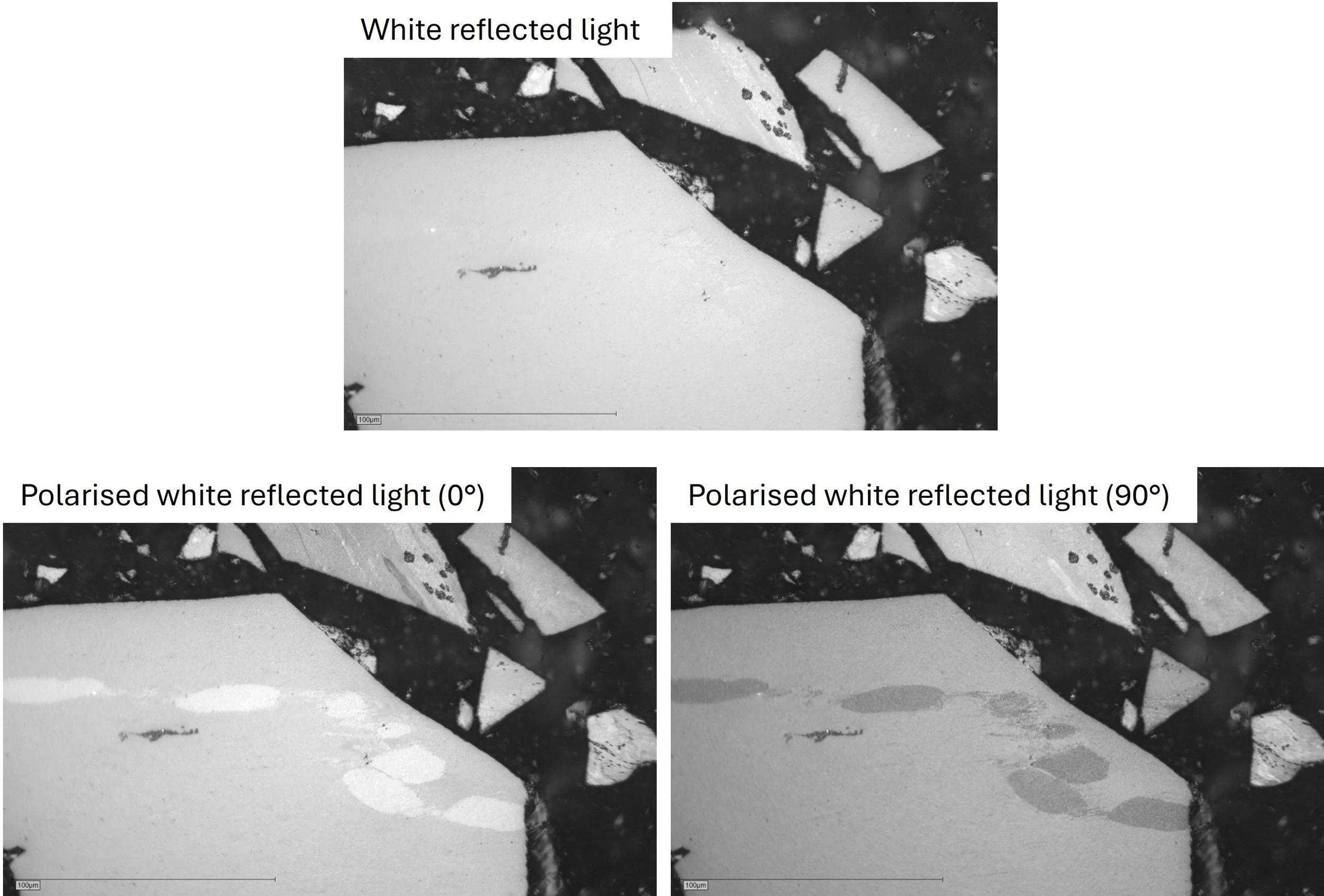

Take these examples. The resinite ovoid-shaped bodies are barely noticeable under plain white light. You need a trained eye to spot them. But when you insert the polarizer, they pop out immediately. In this particular case, the reflectance of the liptinite (resinite bodies) matches that of the surrounding vitrinite. However, its optical anisotropy is quite distinct. It turned out that these samples were rich in metaliptinites (an unofficial term for liptinites with a reflectance equal to or higher than that of vitrinite in the same coal).

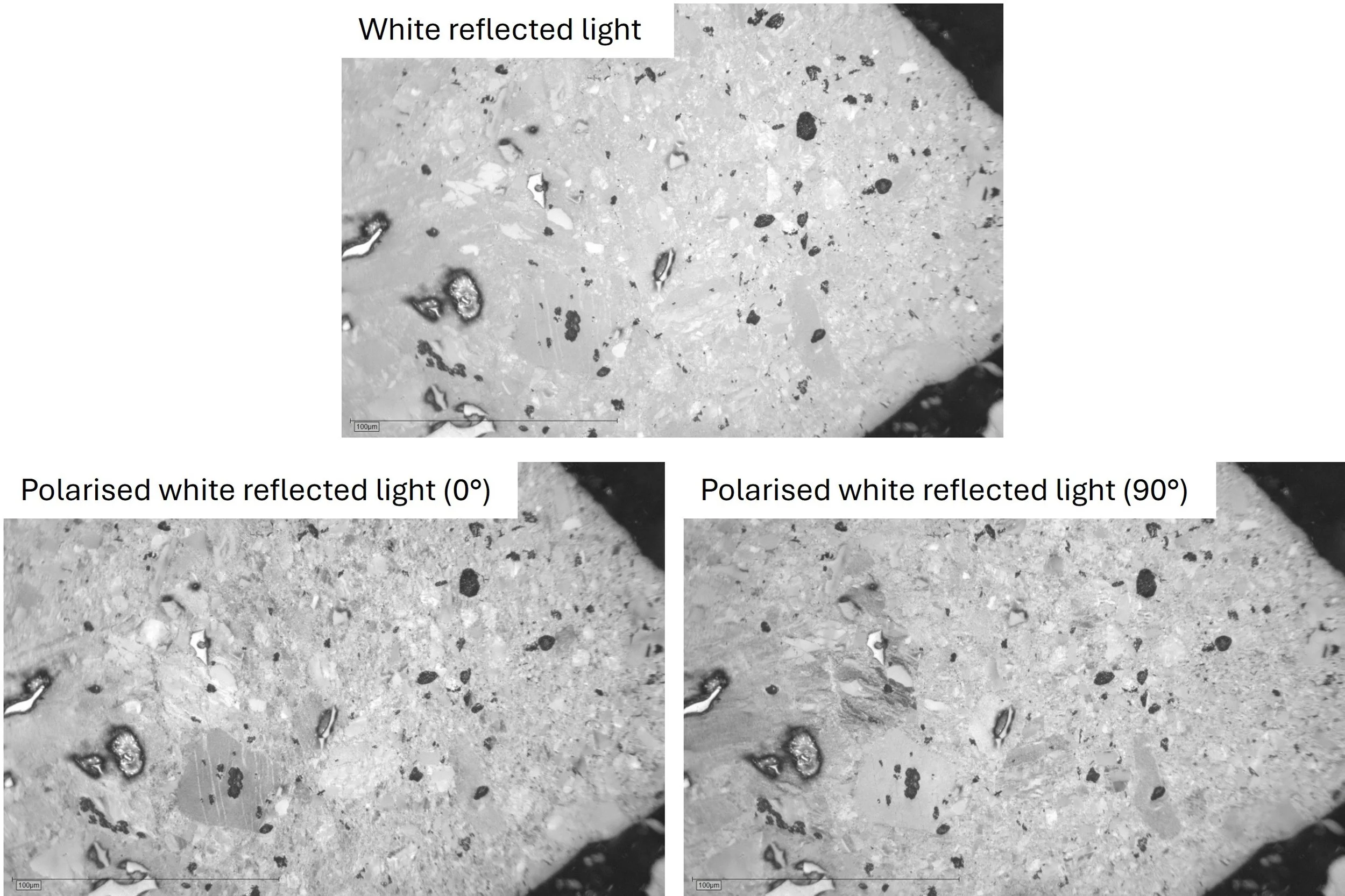

Looking closer, you can also see that the directions of maximum illumination (at 0°) and minimum illumination (at 90°) are the same for both vitrinite and meta-resinite, albeit with different intensities. This indicates that both organic materials reached their maximum coalification stage under the same stress orientation. However, in the next set of figures, the illumination extinction differs between particles. This suggests that these particles attained their maximum coalification degree before being broken and reassembled into a brecciated particle. Polarized light also reveals evidence of thermal alteration due to the emplacement of an igneous body—something that would be difficult to detect under plain white light alone.

This is what I do. I look under the microscope, and I know things. Observations like these have implications for paleoenvironmental reconstructions, geological interpretations, and technological studies. A standard maceral analysis might overlook these details entirely. Of course, petrographic observations are often open to interpretation—what one petrographer sees, another might question. But careful observation, combined with experience and context, helps uncover the most accurate story a sample can tell.

Petrography is both a science and an art—attention to detail can reveal stories that might otherwise go unnoticed and answer to questions on why samples behave in a certain way. At CarbonMat, this attention to detail is what sets my work apart—because the smallest observations can lead to the biggest insights.